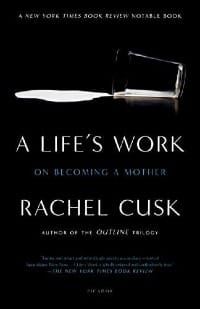

Rachel Cusk, A Life's Work

Rachel Cusk's A Life's Work is an insightful, honest, and sometimes hilarious account of pregnancy and early motherhood. The author tells the story of her own metamorphosis from independent entity to "motherbaby" unit in rough chronological order: from the alarmist literature of pregnancy, which "bristles with threats and the promise of reprisal" for expectant mothers who violate dietary prescriptions; to the propaganda of natural childbirth advocates ("Some women find birth the most intensely pleasurable experience of their lives"), those souls who maintain that a procedure akin to, say, squeezing a cantaloupe out of one's anus can be rendered nearly pain-free, indeed "pleasurable", by the simple adoption of an embarrassing breathing technique; to a mother's shocking, sudden immersion into an alien world of sleeplessness and isolation. (The immediacy of the metamorphosis is brought home to the author soon after she delivers her daughter by caesarian: "Do you want to try putting her to the breast? the midwife enquires as I am wheeled from the operating theatre. I look at her as if she has just asked me to make her a cup of tea, or tidy up the room a bit. I still inhabit that other world in which, after operations, people are pitied and looked after and left to recuperate.")

Cusk's account is a quick read, her prose very often elegant. She hits a number of nails squarely on the head—in her descriptions of the constant demands made on breastfeeding mothers, for example, or the drama and tension inherent in bringing a baby out into the public, or one's cautious anticipation of freedom when it looks like the kid may finally sleep. She talks about the parents' eventual containment in a single, safe room once the baby changes "from rucksack to escaped zoo animal," an alteration in lifestyle that expectant parents, reading the standard parenting books, would not likely anticipate. Cusk describes, perfectly, the "mess and endemic domestic chaos" of a child-occupied house, "which no amount of work appears to eradicate." And she details for the non-parent, wont to lie in of a Saturday morning, what weekends are like for parents:

"What the outside world refers to as 'the weekend' is a round trip to the ninth circle of hell for parents.... You are woken on a Saturday morning at six or seven o'clock by people getting into your bed. They cry or shout loudly in your ear. They kick you in the stomach, in the face. Soon you are up to your elbows in shit—there's no other word for it—in shit and piss and vomit, in congealing milk."

Cusk is at her best when describing parenthood in scenes such as the above. Less successful are the more philosophical passages of the book (the female is "a world steeped in its own mild, voluntary oppression, a world at whose fringes one may find intersections to the real: to particular kinds of unhappiness, or discrimination, or fear, or to a whole realm of existence both past and present that grows more individuated and indeterminate and inarticulatable as time goes by") and the strange inclusion and discussion of parenthood-related literary passages culled, for example, from Jane Eyre and Edith Wharton's The House of Mirth.

A lot of people could benefit from reading Cusk's account. New mothers will find solace, perhaps, in its pages, validation of their own feelings of isolation and resentment. Working fathers ought to read it, so they can better understand the complaints of their shut-in wives, for whom "work is considered an easy, attractive option." And the childless friends of parents will find the book a highly readable explanation of what is happening in their friends' lives.

Member discussion