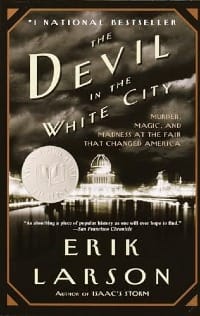

Erik Larson, The Devil in the White City

In the early years of the 1890s, thousands of men labored feverishly under an all-but-impossible deadline to erect an ephemeral masterpiece, the Chicago World's Fair, which would be open to the public a scant six months, from May to October of 1893. Principal among those at work on the exposition was chief architect Daniel Hudson Burnham, who did a yeoman's job in overseeing the minutiae of the construction. Prominent also was the nitpicking landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who already had on his resume the design and construction of New York's Central Park.

People flocked to Chicago while the Fair was being prepared: able-bodied men who were looking for sure work in a period of economic depression; young women leaving home for the first time to seek employment as secretaries or teachers. Chicago may have been a dangerous place—fires alone took a dozen lives a day in the city; and it was aesthetically unappetizing, "a world of clamor, smoke, and steam, refulgent with the scents of murdered cattle and pigs." But the city, particularly during the period of the Fair's construction, offered opportunity.

One man, for example, the handsome and blue-eyed and oddly magnetic Mr. H.H. Holmes, discovered that the influx of young naifs to Chicago provided him with a surfeit of prospective "material." That is, with a great number of young women, newly uprooted from their families, renting rooms in the hotel he had constructed near the Fair grounds, it became a simple matter for Holmes to find women he could murder and either cremate in his home-made kiln or flay and have turned into articulated skeletons. Late-19th-century Chicago was indeed a place where dreams could come true.

In The Devil in the White City, author Erik Larson weaves together the story of the Fair's construction and an account of Holmes's criminal career. (The man's villainy, though manifest throughout, becomes a visceral thing only near the book's end.) Both halves of the tale are fascinating. In addition to being (pleasantly?) repulsed by the grotesqueries detailed, readers will come away from the book having learned an enormous amount about the Fair and its background. (The mark the Fair left on American society is still in evidence: both the Ferris Wheel and Shredded Wheat had their start at the exposition, and readers may be surprised that we also owe to the fair that little ditty that's played as background music in movies with Middle Eastern snake-charming-type scenes.) My only criticism is that Larson sometimes provides too much detail. He thrice provides the menus of banquets attended by the principals, for example. Otherwise, a rewarding read.

Member discussion